Craigmount High School Pipe Band - I’m Third Row Down Far Left

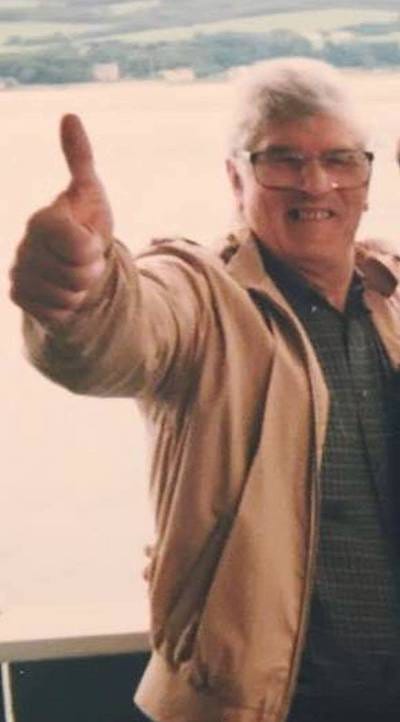

My journey with the pipes began in the gentle corners of childhood, in the living room of our home in Bathgate. I was around seven or eight years old when my father, Danny Connor, began to leave a practice chanter in strategic places around the house. It was an invitation disguised as a simple object. My father, a world champion with the Shotts and Dykehead Caledonia Pipe Band, had a knack for nurturing talent subtly. The chanter, resting innocuously among the sofa cushions or propped against a chair, was never just a toy—it was an invitation to explore a legacy.

I remember picking up the chanter for the first time, intrigued by its strange, hollow sound. My father would gently suggest that I try the scale, guiding me through the notes with a patient and encouraging tone. It was clear from the beginning that this was not merely about learning an instrument; it was about connecting with a tradition. My father’s influence was profound, and his quiet encouragement set the stage for what would become a lifelong passion.

Recognizing my burgeoning interest, my father enrolled me in learning classes at Boghall and Bathgate Pipe Band. There, under the tutelage of Pipe Major Bob Martin—a close friend of my father—I began to hone my skills. Pipe Major Martin was a figure of considerable stature in the piping community, and his instruction was a mix of technical precision and artistic nuance. The lessons were rigorous, and I quickly learned that playing the pipes was as much about discipline as it was about musicality.

However, our family’s move back to Edinburgh marked the end of my time at Boghall and Bathgate Pipe Band. The transition was bittersweet, and with it came a period of abandonment for the chanter. For a while, the instrument was set aside, its melodies silenced as I adjusted to new surroundings. Yet, the seed had been planted, and the desire to play remained, even if it lay dormant for a time.

A couple of years later, my passion for piping was rekindled. My father, ever the dedicated mentor, took a more hands-on approach, tutoring me himself. His commitment to my development was unwavering. He guided me through the complexities of the instrument, refining my technique and deepening my understanding of piping. His lessons were rigorous and thorough, designed to elevate my skills to a high standard.

It was during this period of intense practice that I joined Craigmount High School Pipe Band, located not far from our home in East Craigs. The band was a vibrant community of young pipers, and I quickly became immersed in its rhythms and routines. My participation in the Novice Juvenile Pipe Band introduced me to the competitive side of piping. We took part in various contests, and I relished the opportunity to test my skills in a formal setting.

One of the most memorable experiences of this period was my first solo piping contest at Bellahouston School in Glasgow. I had recently sustained a broken leg while playing football for Salvesen Boys Club, an injury that allowed me to stand still during the performance instead of marching. The judge for the contest was Harry McNulty, the Pipe Major of the Edinburgh Police Pipe Band. Despite the pain and the limitations imposed by my injury, I managed to perform, and perhaps it was this display of perseverance that earned me a fourth-place medal. McNulty’s decision to award me a place, despite the challenges I faced, felt like a validation of my efforts and courage.

As I reached the age of fifteen, my focus began to shift towards football. My dream of becoming a professional footballer took precedence, and I left the pipe band to concentrate on the sport. Yet, even as I pursued my new passion, the chanter remained a constant companion. Twice a week, I accompanied my father to Shotts and Dykehead Pipe Band practices. During the car journeys, I played the chanter, and my father’s presence was a comforting reminder of the discipline and dedication that had been instilled in me.

My father’s guidance during these journeys was both precise and motivational. He would listen intently, correcting my mistakes and reinforcing a crucial lesson: if I made an error, I was to stop, correct it, and play the phrase again. This approach, which emphasized accuracy and persistence, became a cornerstone of my practice and shaped my understanding of musical excellence.

Recognizing my growing proficiency, my father decided to seek further instruction for me from a remarkable piper: Charles MacLeod Williamson. Charlie Williamson was a highly respected figure in the piping community, known for his intricate compositions and deep musicality. He had been a family friend since the 1950s, and my father held him in high regard. Charlie’s work for Edinburgh Corporation Transport, where he used a broom handle to trial his compositions before transcribing them, was a testament to his unique approach to music.

Charlie MacLeod Williamson.

Charlie Williamson’s compositions, particularly his jigs and 6/8 marches, were celebrated for their complexity and beauty. However, many of his tunes were published with alterations that did not reflect his original intentions. Gracenotes and phrasing were often changed, much to Charlie’s dismay. He was a purist, and he believed that every detail of his compositions was crucial to their authenticity.

When I was at a young age, my father asked Charlie if he would take me on as a pupil. Charlie, known for his introverted nature, initially hesitated but ultimately agreed. My weekly trips to Clermiston, where Charlie lived, became a cherished routine. Regardless of the weather—rain, hail, or shine—I would cycle from East Craigs for what were nothing short of master classes in music composition, technique, and the rich oral history of piping.

Charlie’s lessons were a blend of technical instruction and storytelling. He would describe the origins of each tune, the emotions that inspired them, and the historical context behind their creation. His deep connection to the music was palpable, and his compositions often reflected profound personal experiences. One notable example was a full orchestral suite he composed about the Aberfan mining disaster, a piece that used the pipes as the central instrument to convey deep emotions.

Lessons with Charlie were more than just music lessons; they were a window into his world. We would often start with a chat about politics, the labor movement, and sometimes share cake and tea with his wife. After these conversations, we would delve into practice. Charlie’s talent extended beyond the pipes; he was also an accomplished clarinet player. His musical abilities were evident in every aspect of his teaching.

Charlie’s son, who became a music teacher and performed in top orchestras, never took up the pipes. This background, coupled with Charlie’s own musical legacy, likely influenced his decision to accept me as a student. Through our lessons, Charlie passed on his life’s work in piping, sharing his compositions and insights with me. His wife, a gifted pianist, added another layer of musicality to their home, creating an environment rich in artistic inspiration.

I always referred to Charlie as “my other father.” This affectionate nickname reflected the profound influence he had on my musical development and my life. His guidance was akin to that of a second father figure, and his impact on my understanding of piping was immeasurable. Charlie’s role in my life went beyond that of a teacher; he was a mentor, a friend, and a source of inspiration.

Charlie Williamson’s compositions, particularly his jigs and 6/8 marches, were celebrated for their complexity. However, many of his tunes were published with alterations that did not reflect his original intentions. Gracenotes and phrasing were often changed, much to Charlie’s dismay. He was a purist, and he believed that every detail of his compositions was crucial to their authenticity.

One of Charlie’s most well-known compositions, “Granny MacLeod,” was simplified in print, losing much of its original phrasing and intricate gracenotes. Charlie was deeply dissatisfied with these alterations, as they diminished the essence of his work. The tune, composed when he was just fourteen, had been written in his grandmother’s bedroom and came to him in a burst of inspiration. The original version, complete with its detailed gracenotes and phrasing, held a special place in Charlie’s heart.

I had the privilege of learning from Charlie directly, and his influence was profound. Tunes that he wrote, recorded in a handwritten green music book, were complex and intricate. Each lesson involved selecting a tune from this book, writing it down in my own music book, and understanding its structure and nuances. Charlie emphasized the importance of playing the tune as it was written, avoiding reinterpretation for ease. His teaching went beyond technical skill; it was about preserving the integrity of the music.

In later years, I joined the Scottish Gas Pipe Band under Gordon Campbell. Charlie’s involvement with the band rekindled his enthusiasm for piping. He was pleased to see his music appreciated by a new generation of pipers. Several of his tunes were recorded on the band’s album, and it was heartening to know that his legacy continued to resonate. Stevie McDonaugh, a former member of the band and a friend of Charlie’s, played a significant role in ensuring that Charlie’s contributions were recognized and celebrated.

Reflecting on my journey with the pipes, I see a tapestry woven with the guidance of my father, the wisdom of Charlie Williamson, and the enduring passion that has driven me throughout the years. Each note, each lesson, and each memory is a testament to the rich history and profound impact of the piping tradition. The echoes of the chanter, the lessons learned, and the music created form a narrative that connects the past with the present, honouring the legacy of those who came before and inspiring those who will follow.

The road from the living room in Bathgate to the stages and contests where I performed has been shaped by the influence of two remarkable figures: my father and my other father, Charlie Williamson. Their legacies are etched into every note I play, and their guidance continues to inspire me as I navigate the ever-evolving world of piping.

The town of Shotts, nestled in the heart of Scotland, was the canvas upon which my teenage years unfolded. It was a place where the echoes of bagpipes and the rhythmic beats of drums painted the air with a musical legacy that transcended borders. My father, a devoted member of the world-renowned Shotts and Dykehead Pipe Band, was not just a piper; he was a custodian of a rich tradition that spanned generations.

As a youngster, I found myself enveloped in the ethereal sounds of bagpipes and the camaraderie of legends. Names like Tom MacAllister, Alex Duthart, Drew Duthart, Bertie Barr, Jim Kilpatrick, Robert Mathieson, Davie and Jim Hutton, Bill Shearer, Arthur Cooke, John Scullion, John Barclay, Bob Leitch, Donald Thompson, along with my father, Danny Connor—these were not just names; they were the maestros, the wizards of melody, and they were the stars that adorned my teenage sky.

Weekly rituals involved accompanying my father to band rehearsals, an odyssey that transported me to a realm where the music was a language spoken with passion and precision. It was a world where dedication and discipline met the soul-stirring notes that reverberated in the heart of Shotts.

Shotts & Dykehead Caledonia Pipe Band - Pipe Major Tom McAllister and Leading Drummer Alex Duthart. My Father is Back Row Second From Left, Next To Pipe Major Tom McAllister.

One particular Hogmanay, etched vividly in my memories, unfolded on the stage of Motherwell Civic Centre. The Shotts and Dykehead Pipe Band, resplendent in their regalia, cast a spell on a television audience. The afterparty, a clandestine gathering of musical luminaries, was a spectacle in itself. Scottish legends Peter Morrison, Moira Anderson, The Corries, along with Alasdair MacDonald, shared the spotlight with the band.

Shotts and Dykehead Caledonia Pipe Band was, and still is, a well-known and successful pipe band based in Shotts, North Lanarkshire, Scotland. The band was formed in 1910 and has a rich history of achievements in the world of competitive pipe band music. Shotts and Dykehead is particularly renowned for its success in Grade 1, which is the highest level of competition in pipe band rankings. The band has won numerous championships and accolades over the years, and it is often considered one of the top pipe bands in the world. They have a strong reputation for musical excellence and have contributed significantly to the promotion and preservation of Scottish bagpipe music.

The Corries, a Scottish folk music duo composed of Roy Williamson and Ronnie Browne, were active from the early 1960s until Roy Williamson's death in 1990. They gained popularity for their unique blend of traditional Scottish folk music, humour, and social commentary. Roy Williamson played the guitar, mandolin, and various other instruments, while Ronnie Browne was known for his vocals and guitar playing. One of their most famous songs is "Flower of Scotland," which has become an unofficial national anthem for Scotland. The Corries' music often reflected Scottish culture, history, and a love for their homeland. Despite Roy Williamson's passing, Ronnie Browne continued to perform and promote their music after the duo disbanded. The Corries left a lasting legacy in the Scottish folk music scene.

Amidst the revelry, my father took centre stage, standing on a table as he regaled the gathering with Bothy Ballads passed down through generations. The room echoed with applause, and the tales of the bothy resonated with the very spirit of Scotland. It was a moment when the threads of tradition wove seamlessly into the tapestry of contemporary celebration.

The Corries.

Life in Bathgate, a quaint town, provided the backdrop for some of the most surreal moments of my adolescence. Invitations from Ronnie and Roy of The Corries were the stuff of dreams. We were ushered backstage, treated like royalty, and I, a wide-eyed teenager, collected autographs from the living legends.

Yet, the surrealism didn't end there. On one occasion, I found myself perched at the top of our home's staircase, a silent observer to a scene that seemed straight out of a novel. My father, in the heart of Bathgate, conversed over the phone with Ronnie and Roy, who were miles away, recording the Bothy Ballads he sang down the line. The very walls of our home seemed to resonate with the history being made, a harmonious collaboration spanning time and space.

The words my grandfather once sang found a new home in the melodies of The Corries, immortalised in future set lists that bore witness to this transgenerational musical dialogue—"The Wheel Of Fortune" and "The Wedding Of Lachie McGraw."

In those moments, as a teenager in Bathgate, I realized that life had composed for me a symphony of memories, each note resonating with the harmony of tradition, the thrill of the present, and the promise of a future steeped in the timeless tunes of Shotts and Dykehead.

During the times I would follow my father to Shotts practices, it offered me a window into the top-class players, legends, and personalities my dad was mixing with. The opportunity to witness the masters at work, to see their dedication, and to hear their stories was an invaluable part of my upbringing. It wasn’t just about learning to play; it was about understanding the heritage and passion that fuelled the music. This immersion in the world of Shotts and its legendary players enriched my perspective and deepened my appreciation for the artistry and tradition that define the world of piping.

What are Bothy Ballads?

I referred to Bothy Ballads in the narrative, here is an explanation as to what they are. Bothy Ballads are a distinctive genre of Scottish folk music that originated in the rural communities of Scotland, particularly in the Northeast. The term "bothy" refers to a traditional Scottish rural building used as a shelter for farm workers, and the ballads were originally sung by these workers to pass the time during their labor.

1. Origins and Context: Bothy Ballads emerged in the 18th and 19th centuries, rooted in the agricultural practices of Scotland. Bothies were simple, communal living spaces for agricultural workers who were employed seasonally to harvest crops or perform other farm tasks. The ballads served as a form of entertainment and storytelling among these workers. The songs often recounted tales of love, loss, and humor, and provided a sense of camaraderie and shared experience.

2. Musical Characteristics: Bothy Ballads are characterized by their straightforward, narrative style. They typically feature a simple, repetitive melody that is easy to remember and sing along to. The lyrics are often narrative-driven, recounting humorous or dramatic stories from everyday life. The songs usually employ a call-and-response structure, making them interactive and engaging for listeners.

3. Themes and Content: The themes of Bothy Ballads are varied but frequently revolve around rural life and experiences. They might include humorous anecdotes about farm life, romantic entanglements, or tales of social and political events. The ballads often reflect the resilience and wit of the rural workers, providing a snapshot of their daily lives and struggles.

4. Preservation and Popularity: Bothy Ballads have been preserved and popularized by folk musicians and enthusiasts. While their origins are humble, these songs have become a cherished part of Scotland's cultural heritage. Prominent folk artists like The Corries and other traditional musicians have played a significant role in bringing Bothy Ballads to a wider audience. The tradition continues through performances at folk festivals, recordings, and community gatherings.

Bothy Ballads and Their Significance

Bothy Ballads hold a special place in Scottish cultural history. They represent a form of folk expression that captures the essence of rural life and the communal spirit of the bothy. Through their storytelling and musical simplicity, they offer a glimpse into the lives of Scotland’s agricultural workers and the traditions that shaped their experiences.

Share this post